- Home

- Christopher Goffard

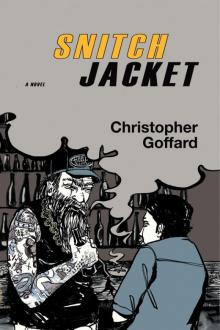

Snitch Jacket

Snitch Jacket Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

PART I - THE OUTLAW

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

PART II - THE COWBOY

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

PART III - THE POET

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

PART IV - THE FIX

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

CHAPTER 31

CHAPTER 32

CHAPTER 33

CHAPTER 34

This edition first published in The United States of America in 2007 by

The Rookery Press, Tracy Carns Ltd.

in association with The Overlook Press

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

Copyright © 2007 Christopher Goffard

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review. The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and strictly prohibited.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN : 978-1-590-20747-5

To Jennifer, Julia, Sophia & my parents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to thank the following people for their friendship, feedback, and/or random gifts of inspiration, which proved invaluable in writing this book: Jesse Wilson, Danny Wein, Andy Conn, Chuck Natanson, Will Fischbach, Bill Varian, Mark and Anne Albracht, Graham and Nicole Brink, Robert Eldred, Darren Madigan, Gary and Inge Bortolus, Jamal and Sami Thalji, Charley Demosthenous, Sean Keefe; special thanks to Seth Jaret, my manager; my agents Phil Patterson and Luke Speed; James Gurbutt, my editor; my parents; and my wife Jennifer, above all.

snitch jacket ’snich ‘ja-ket noun: slang term denoting the state of being an informer; believed to have a jailhouse origin stemming from the distinctive colors worn by informers in protective custody; considered pejorative; see also: snitch, informer, confidential informant, C.I., sing, stool pigeon, squealer, squeaker, squawker, narc, songbird, rat

‘Snitches are a dying breed.’ – Outlaw Biker saying

PART I

THE OUTLAW

CHAPTER 1

The big man lived in the janitor’s closet behind the bar, and through the night you could hear him building birdhouses. He sawed and hammered in his tiny room, using scraps of pine and cedar and aluminum foraged from flea markets and junk piles. His knuckles grew together in knobby masses, they’d been broken so many times, but over the wood his hands ran rhythmically, sanding and smoothing. Finished, the birdhouses looked as fragile and crushable, cradled in those lumpy sledgehammer mitts, as the eggs of the phantom fowl they were supposedly meant for. They hung from the ceiling and piled up on his padlocked ice-chest and foot-locker, alongside his cigar box of war souvenirs and photos of Army buddies. By daybreak he’d be flat on his mattress gazing dead-eyed at the empty aviaries, each one dustily returning his stare with the single neat blind eye he’d bored in its middle. By mid-morning he’d be asleep, sawdust filming his beard and the gray coat of his ancient dog, Jesse James, dozing beside him on a Mexican blanket.

No one knew for sure, but we supposed the big man had picked up his hobby in some prison woodshop, the same way his body had collected ink from Soledad to Starke. He wore patriotic eagles and vampire bitches, Old Testament prophets and pitchfork devils. His tattoos were like stickers commemorating ports of call on an enormous, beaten suitcase. They crowded each other, overlapped, got jumbled up. The names he’d worn over the years sometimes got jumbled up too. By the time he came to live in the bar he was calling himself Gus Miller.

Mad Dog Miller’s legend preceded him. ‘Mad Dog lobotomized a whole squad of Vietcong with a chopstick,’ people whispered. And: ‘Mad Dog survived six weeks in the Khe-Sanh mountains on his own urine.’ The first look you got of him – the gimlet eyes blazing through crooked glasses, the crimson face with the riot of exploded veins, the gigantic tar-streaked Norse-god beard – well, you could even believe it. Bedlam in the bones, his face proclaimed.

One of his birdhouses, a nice little Tudor cottage job, is sitting now on the sill of the 11-by-7½-foot cell where I’m writing this as a guest of the State of California. It makes me miss the big man, though of course I wouldn’t be in this brick-and-razorwire snakepit if he hadn’t lumbered into the Greasy Tuesday with his dog and his million stories and his movie-house sentimentality.

The night I first saw him, he was throwing his war medals against the wall and wearing a necklace of human ears. I knew right away I wanted to be his friend.

CHAPTER 2

My public defender’s name is Walter Goins. You’d think it rhymes with loins, from the spelling, but it’s pronounced go-ins. Gut, combover, firesale suit, Looney Tunes tie: he does not inspire confidence.

We’re sitting in an interview room with a stainless-steel table between us and I’m trying to make him understand the horrible wrongness of my situation. I share a filthy brick cell, and a lidless toilet, with three other guys awaiting trial: a gabby junky with sores on his arms; a schoolteacher facing vehicular manslaughter who weeps in his sleep; and a swastika-covered teenager who stabbed his girlfriend’s mom with a chlorine-filled syringe. They’re all resigned to it, one way or another. You can see it in their eyes, the knowledge that their lives pointed here, right here, all along; it’s a kind of comfort to arrive.

‘I’m not like these others,’ I tell Goins. ‘I don’t belong here.’

‘You’ve been in lockup before, right?’ Goins says.

‘Few months in county jail here and there,’ I say. ‘I can hack it for a while. But state prison? Christ, Goins, they send me there, you could measure my life with an egg-timer.’

First they push you into a broom closet. Then they bust out your teeth and take turns while you kneel. Then they cut out your tongue and say, ‘You won’t talk to pigs no more, even in hell.’ Then they slip the shank, and by then, you’re glad to say: So long.

Goins is all that’s standing between me and that broom closet. But his tie is making me insanely insecure, a reminder of how utterly fucked I am. Clear sign he’s a public defender – no one would hire an attorney in a Looney Tunes tie – and he wears it like a defiant sneer.

‘What are you, a pediatrician?’ I say in a half-joking tone meant to conceal my nervousness. ‘Of course, my broke ass, I get you gratis, so who am I to complain how you dress?’

‘It’s a grim life,’ Goins says flatly, fingering the tie. ‘Why not?’

‘A little sartorial whimsy, sure, I appreciate that. Life is pretty grim. Except mine is in your ha

nds here, Goins. You understand? Mine is in your hands.’

‘I take my responsibility to my clients very seriously, but I try not to take myself too seriously. There’s a distinction, you know.’

He watches me with chill, suspicious eyes as if I were some kind of repellent rodent. The look tells me I’m just another imbecile client, tells me Goins sees what almost everyone else sees: a short, unscrubbed man with bad posture, bad teeth, and jittery, chemically damaged eyes that are set a little too close together – the kind of guy he unconsciously edges away from in the elevator, one no Girl Scout ever approached with a box of cookies. An antisocial personality who, save for the manacles bolting his hands to the table, might lunge across and stick a Bic pen in his lawyer’s eye.

‘I’m not at all what you think,’ I say in a kind of angry panic. ‘I always had ambitions.’

I explain that I could’ve been a lot of things, had I put my mind to it. Maybe a history professor. I love history. I know a lot about it.

‘In a game of Trivial Pursuit,’ I say, ‘I’m pretty sure I could go toe-to-toe with you, even though you’re almost a lawyer and I’m just an ex-dishwasher at a Mexican restaurant facing Murder One. Did you know the Aztecs imbibed their beer anally during religious festivals? Aztec Empire, 1325 to 1521. Good to know history.’

A cop is another thing I could’ve been, I explain, really the main thing I wanted to be. One of those detectives who swishes into a crime scene – he’s got a bad-ass overcoat, so he swishes – and sees what everyone else misses. ‘What we need on these bullets,’ he says, ‘is some Neutron Activation Analysis. And don’t forget to run the ICPs.’ I tell Goins that’s short for Inductively Coupled Plasma Optimal Emission Spectroscopy Analysis.

‘I bet you never had a client who knew that, have you, Goins?’

‘I guess not.’

‘It’s good to know science.’

‘Why are you telling me this?’

‘I’m not one of these low-lifes,’ I say. ‘You think I couldn’t be a lawyer, if I’d put my mind to it? Not just a PD, either: a real one. Double-breasted suits, new tie every day of the year, Mont Blanc pens – that’s the name of a high-end pen – with a few little diamonds in it, maybe, that flashed when I pulled it out to sign something. Cufflinks with double Bs: Benny Bunt. My watch? Emporio Armani job, cutting edge: no numbers, no hands. Maybe a Timex in my pocket to actually tell the time with. Salvatore Ferragamo, Louis Vuitton: Italians crawling in every orifice. That’s what I’d look like, if I were a lawyer.’

He doesn’t find any of this funny. Cuttingly I add: ‘Always figured I’d be a prosecutor, on the side of the good guys.’

He smiles icily. ‘Well,’ he says, ‘it’s the good guys who want to stick a needle in your arm filled with sodium chloride. The scientific term is “joy juice”.’

He seems to sense that I’ve been testing his stones, trying to measure the fight in him.

‘Look,’ I say, ‘I didn’t mean to insult you. The truth is, I’m embarrassed by how much I want you to like me. You’re my Destroyer Lawyer. You’re my Demon Barrister. And I have absolute faith,’ I lie, ‘that you’re going to find a way to get me out.’

Goins’s eyes don’t change; his face doesn’t twitch; he genuinely doesn’t care whether I believe in him or not. I fear I have already alienated him beyond repair, squandered what little goodwill he might have brought to the table.

‘You seem to have some education,’ Goins says.

‘Three semesters at Costa Mesa Community College. I was going for a degree in Criminal Justice.’

‘What happened?’

There’s a lot I could tell Goins. Like how by the time I enrolled, in my mid-twenties, I’d been surviving on my own for 10 years, drifting in and out of juvie halls and county lockups, mostly on charges related to an on-again, off-again attachment to crystal meth. I could tell him how it’s tough to concentrate on your midterms when you’ve been up for 50 hours straight, fingering nuts and bolts, dismantling your roommate’s toaster, and clawing through Dumpsters for aluminum cans (not for the pennies they bring, although this helps buy more powder, but to satisfy the mysterious tactile jones every meth monster knows).

No, college wasn’t for me. I could tell Goins about all I learned from a guy I met at the Van Nuys public library, a retired professor named Ray Castle, whose couch I crashed on until I realized he had ancient Greek notions of what a mentor – pupil relationship should be. I could tell him about the six different law-enforcement agencies that rejected my applications for employment, as cop, as dispatcher, even as clerk. I could catalogue for him the jobs I’ve worked and lost – short-order cook, furniture-hauler, lawn boy, telemarketer, Blockbuster Video clerk, assistant at a one-hour photomat, ice-cream scooper at Baskin Robbins, Radio Shack stock boy – and point out how a rap sheet and no degree makes it tough to get much better.

Or I could admit that I’ve always found a kind of security in dead-end jobs, because as long as I could tell myself I was just slumming, just logging time in a temporary gig that didn’t come close to defining me, well, maybe I wasn’t out of the ballgame yet. Like an actor who’d rather wait tables than teach junior-high drama: the first job means he’s waiting to arrive, the second that he’s given up all hope of arriving. Instead I say, ‘I wasn’t a college type of guy. Plus, two jobs in the world let you do all the reading you want. One’s bum. The other’s jailbird. I’ve been both. Once read a dictionary page-by-page during a six-month jail stint, made it all the way to the Rs. Got the idea from Malcolm X.’

He flips open a yellow pad. He says, ‘Well, let me stack it up for you. We have a man in the Mojave Desert with a bullet in him, and your prints on the gun. We have another guy burned beyond recognition, and you the last person seen in his company. And we have a third guy being thawed out now like a Neanderthal in an ice-slab, found in a vehicle you were driving. In short, Benny, the stage is ass-deep in corpses. And you’re ass-deep in trouble. First-degree murder, felony murder, conspiracy to commit murder – – ’

Suddenly it’s hard to breathe, and I say, ‘Goins – Goins – that’s not me.’

He looks at me, blinking, as if astounded by the zeal of my denial.

‘Okay,’ he says. ‘Alright. I’d like to believe you. All I can do is ask you to tell me the truth. I don’t really expect you to – no one does – but it’s you who gets the screwing if you lie. We’ve got exactly four days till your prelim. That’s where the state puts on a preview of its case, and the judge decides whether there’s probable cause to bind it over to Superior Court for trial.’

‘I know what a prelim is.’

‘It’s our chance to blow the case out of water, early. Although I’m not gonna lie about the odds.’

‘What do you need from me?’

‘Everything you can tell me – anything even remotely relevant to the case. Anything else that’ll help me understand the world from inside your skull. If I’m going to make a judge and jury empathize, I need to feel it. I mean, I can fake it, but I like to feel it. I want to be able to write a book about you. Pretend I’m a bird on your shoulder, seeing and hearing everything. Alright? So start. Start where it starts.’

‘The Greasy Tuesday.’

He clicks his pen and starts writing. ‘It started on a Tuesday?’

‘I couldn’t say, Goins. I’m telling you the place’s name.’

CHAPTER 3

The Greasy Tuesday is a one-room, sawdust-floor dive on Harbor Boulevard in Costa Mesa, on a block the Orange County Chamber of Commerce will never allow to blight a postcard. Scrub shops, check-cashing joints, a Chinese rub-down palace, a porn emporium, a Church’s Chicken, a 99-cent fish-taco stand: you get the picture.

On the corner squats a wholesale wig outlet, and in my Bad Benny days – I mean my adventures-in-amphetamine days – I found myself standing in horror before the display window, with its cloned ranks of bodiless heads. I’d listen to them muttering, trying to form words with their

painted mouths. With a meth-fiend’s paranoia, I believed they were denouncing me, talking some kind of shit. Other times I wept at their helplessness and believed they just wanted a listener, wanted desperately to explain how they wound up in such an asinine limbo. And I’d think, ‘You poor bastards, you’re not alone.’

People say John Wayne used to drink at the Greasy Tuesday. For years he owned a mansion down the hill in Newport Beach, so it was possible, just possible, but I never believed it. Framed behind the cash register hangs a black-and-white photo of the Duke – the leathery older Duke – leaning over a bottle at the scarred, horseshoe-shaped counter of this very bar. Some regulars think the Duke’s head sits at a funny angle on the body, like someone cut it out of a book and glued it on. But they don’t say this around Little Junior, the owner. A rabid Duke-loving American, Junior is, though a terrible failure at eradicating his New Zealand upbringing from his voice.

There might or might not have been all kinds of colorful pistoleros and desperadoes who also figured in the bar’s history. A card shark named Anaheim Ames, who gambled away (and won back) his glass eye a couple of times a year, and whose best friend stabbed him to death over a misheard word . . . a quadriplegic hit-man, Nick ‘Piranha’ Pranwitcz, who lured you close with his one working finger, as if to whisper a secret, only to seize your jugular in the unbreakable vise of his jaws . . . a dwarfish cat-burglar, Hugo Mink, who locked eyes with his heart’s truest yen – a tall, busty, ample-assed woman – the moment his head emerged from the AC vent over her bed, the same tragic Mink who later asphyxiated going down a chimney to steal her an engagement ring . . . a gambler with powers of precognition, Tony the Money, whose hands shook violently when he saw the future and who shot himself after calling a Kentucky Derby superfecta because no one would front him a dime to put on it, his curse being that he couldn’t stay away from the track even when his strange gift wasn’t working . . . and Mad Dog Miller, who persuaded his VC torturers to let him eat his maggoty rice with a chopstick, then used the humble utensil to dispatch the lot of them . . . each name doing service as a kind of empty gigantic foot-locker where people who felt like talking had been putting their stories for years . . .

Snitch Jacket

Snitch Jacket